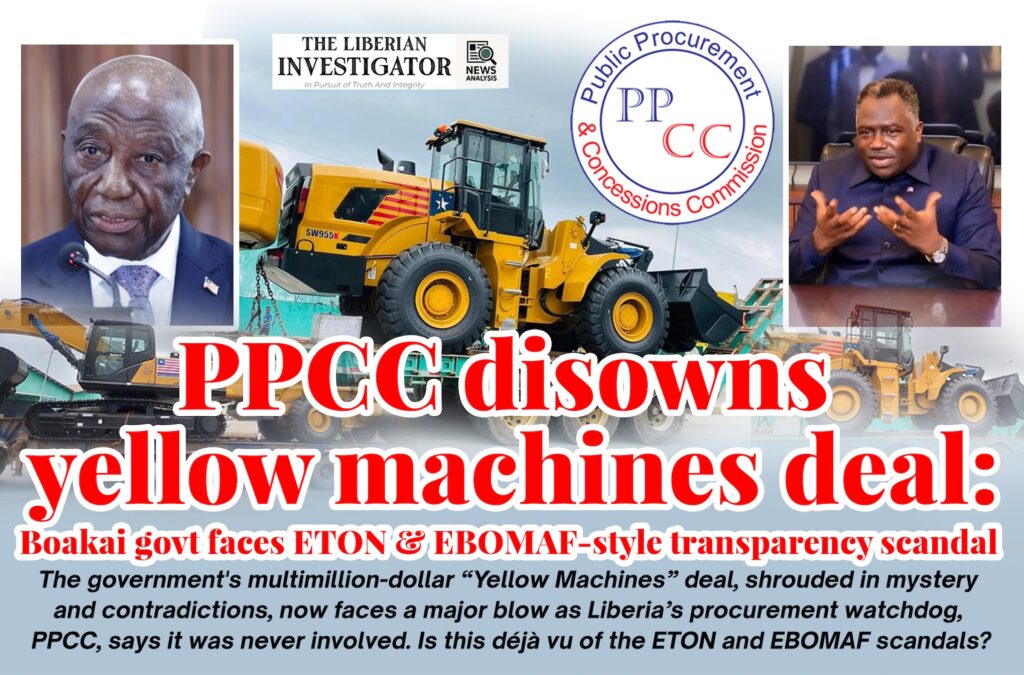

MONROVIA – The Boakai administration’s much-publicized Yellow Machines deal, intended to fast-track Liberia’s road rehabilitation drive, is now in full-blown controversy following startling revelations by the Public Procurement and Concession Commission (PPCC). The Commission says it has no record—zero involvement—in a deal in which the first consignment is already on sea.

Analysis by Lennart Dodoo and David S. Menjor

In an exclusive interview with The Liberian Investigator, PPCC Executive Director Bodger Scott Johnson made it clear: “My office has no record to show that PPCC was involved in any part of the deal. But you can check it out with the Minister of State for Presidential Affairs. They know how they went about it, but it has not reached our office.”

Those 52 seconds of guarded honesty may have just reignited Liberia’s biggest procurement scandal since the ETON and EBOMAF fiascos that marked the early years of President George Weah’s term—two phantom billion-dollar infrastructure agreements later exposed as legally flawed and financially hollow.

Yellow Machines: From Promise to Puzzle

The deal for 285 pieces of yellow-painted earth-moving equipment, originally announced during a May 2024 cabinet retreat, was initially presented as a patriotic gesture between President Boakai and South African billionaire Robert Gumede—chair of the Guma Group.

It was pitched as a gentlemen’s agreement, devoid of formal contracts, legal backing, or legislative authorization. The plan? Deploy 19 machines to each of Liberia’s 15 counties to address the country’s horrific rural road conditions, a critical pillar of Boakai’s ARREST Agenda.

But the arrangement, hailed by Boakai loyalists as visionary, immediately raised eyebrows. No procurement notice. No legislative discussion. No budget line item. No signed documents—at least, not publicly disclosed.

The situation became murkier when the Vice President, Jeremiah Koung, was suddenly announced as the new face of the renegotiated deal. From US$80 million, the cost was slashed to US$22 million. But how and why that reduction happened remains undisclosed.

PPCC: Legally Mandated but Totally Ignored

The PPCC’s primary function is to vet, approve, and oversee all major procurement and concession arrangements involving public resources. According to Liberian law, the Commission must be consulted, and deals of this magnitude must be open to public scrutiny through competitive bidding.

Section 55 of the PPCC Act outlines narrow and specific grounds under which sole sourcing is permitted. None of those appear to apply here.

Yet the government—despite assurances by Information Minister Jerelinmek Piah that the process is lawful—has never published a single document confirming adherence to any of these provisions.

Worse, PPCC’s total exclusion echoes the disturbing precedent of the ETON and EBOMAF loans, where nearly US$1 billion in phantom financing was approved, ratified, and signed without the commission’s input.

Déjà Vu: Echoes of the ETON and EBOMAF Scandals

The Weah-era ETON and EBOMAF loan deals, ratified in 2018, were intended to finance the construction of over 800 kilometers of roads. But as former Finance Minister Samuel Tweah later admitted, “those loans were never disbursed” and the companies involved—especially ETON—had dubious financial histories.

Even the PPCC at the time, under James Dorbor Jallah now the Commissioner General of the Liberia Revenue Authority, was sidelined. Jallah later confirmed the deals violated procurement law and warned the sole sourcing arrangements lacked justification.

Senator Nyonblee Karnga-Lawrence and others moved to have the agreements canceled before they could burden future governments. Ultimately, they were quietly de-ratified.

The common threads are unmistakable: legislative sidestepping, procurement violations, reliance on personal relationships, lack of transparency, and an eagerness to bypass institutions designed to protect public interest.

“My office has no record to show that PPCC was involved in any part of the deal. But you can check it out with the Minister of State for Presidential Affairs. They know how they went about it, but it has not reached our office.”

Bodger Scott Johnson, PPCC Executive Director

The Yellow Machines: Who Is Really in Charge?

Since the first batch of machines arrived in July 2024, there has been no further details to the public as to whether they are being returned or locally sold or perhaps, whether the government has taken ownership. Deputy Minister of State Without Portfolio Mamaka Bility showcased the equipment during the cabinet retreat. She emphasized that this was the “first time since 1980” that Liberia would own its own road maintenance machinery.

Later, the Ministry of State, Public Works, and the Ministry of National Defense were linked to the deployment and maintenance of the equipment.

A two-year maintenance and training agreement was also reportedly part of the original plan.

Minister Bility boasted that over 100 Liberians will be trained to operate the machines.

The Vice President’s Quiet Takeover

With the President under pressure, Vice President Koung was tasked with renegotiating the deal.

Koung reportedly succeeded in reducing the cost from US$80 million to US$22 million in a new negotiation with an undisclosed manufacturer for the same quantity of machines.

Information Minister Piah told journalists that the first tranche of payment had already been allocated in the 2025 budget. Yet when pressed, he deferred specifics to Vice President Koung.

Senator Amara Konneh: From Watchdog to Window-Dresser?

Gbarpolu Senator Amara Konneh, once one of the most vocal critics of the yellow machines, has now offered tepid praise for the restructured deal—if procurement laws are followed.

Former government official Patrick M’bayo condemned the new arrangement as “under-the-table,” and accused Konneh of political expediency.

“From a deal forged in secrecy to a process supposedly championed by the VP—this isn’t transparency, it’s institutional mockery,” M’bayo wrote.

Where’s the Legislature?

Article 34 of the Liberian Constitution explicitly bars the Executive from negotiating loans or financial agreements without legislative approval. Yet at no point did the Legislature publicly debate or approve this deal.

Rep. Musa Bility, among others, took to social media to warn his colleagues that they were complicit in eroding constitutional authority. “This is a pivotal moment. We must act to save our democracy,” he posted.

Even Montserrado Rep. Prescilla Abram Cooper, a ruling party member, conceded that “procedural errors” were made and called for legislative correction.

There are whispers of a retroactive procurement resolution being concocted by Senate allies—a backdated justification to sanitize what many now see as a contaminated transaction.

A Fork in the Road for Boakai

President Boakai ascended to power on a promise to break with the past, to rescue Liberia from the shadows of impunity, cronyism, and disregard for law. Yet here lies a perfect storm of all three.

The arrival of the machines could have been a watershed moment for local development. Instead, it is becoming a mirror of Liberia’s deepest dysfunctions.

If Boakai fails to publish the full agreement, involve the PPCC as the law requires, and open the procurement books to public scrutiny, then history will judge the Yellow Machines deal not as innovation—but as imitation of the very corruption he once condemned.

Discussion about this post